Tribe's link to Taunton essential to casino deal

The Old Colony Historical Society's collection

includes copper and wampum beads used by tribe members for trading and for

self-adornment.Cape Cod Times/Jim

Preston

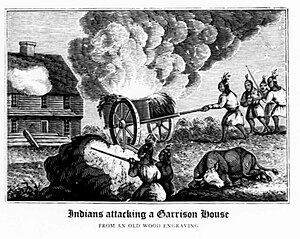

TAUNTON — Hostilities between English

settlers and Native Americans came to a head in this city that now, 331 years

later, is welcoming a tribal casino within its borders.

In

1671, commissioners of the Massachusetts Bay Colony invited Metacomet, also

known as King Philip, the son of Massasoit and then leader of Wampanoag Nation,

to Taunton for a meeting with English settlers, according to S.H. Emery's

"History of Taunton Massachusetts: 1637-1893."

"Philip

was willing to proceed to Taunton Green, then called the Training Field, if

hostages were left. Williams and John Brown consented to remain," Emery

wrote.

Inside an old meetinghouse, colonists stood

on one side in "formal garbs, close shorn hair and solemn countenances," Emery

wrote. On the other side "appeared the tawny and ferocious countenances of

Indian warriors; their long, black hair hanging down their backs; their small

sunken eyes, gleaming with serpent fires ..."

Philip was confronted about reports he was

planning an attack on Taunton and other settlements. "He was covered with

confusion and in his panic acknowledged the truth of all their charges," Emery

wrote.

Philip surrendered his weapons, which

included guns, and "signed his submission," but in the next four years continued

to stockpile weapons for a battle that history now refers to as King Philip's

War.

That history could prove important because

to win federal approval of its proposed $500 million casino project in Taunton,

the Mashpee Wampanoag must

prove to the Bureau of Indian Affairs it has historic and cultural ties to

Taunton.

The tribe is asking the federal government

to take 146 acres in the Liberty and Union Industrial Park into federal trust,

along with 170 acres in Mashpee, for the tribe's initial reservation.

Environmental review

The federal bureau started an environmental

review of the land two weeks ago that is expected to take several months.

Meanwhile, the tribe is negotiating a compact with Gov. Deval Patrick for

payments in lieu of taxes. An announcement could come as early as this week as

the tribe races to meet a July 31 deadline imposed by the state law that

authorizes three casinos and a single slot parlor. The tribe's land into trust

application does not have to be completed by that date.

In a May decision that demonstrates the

importance of the historical ties, the bureau rejected the trust application of

the Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians in California because it did not

"demonstrate it had a significant historic connection to the site."

Making the link between Indians and Taunton

is as easy as walking into the Old Colony Historical Society in the city, where

volumes of books and records are preserved.

But making the connection between the

Mashpee Wampanoag and the territory is not as clear, said William Hanna, a

retired Taunton High School teacher and historian who authored "A History of

Taunton, Massachusetts" in 2008.

Hanna spent hours sifting through records at

the historic society where he says there is no reference in official records to

specific Wampanoag tribes.

"Never, ever have I seen a distinction

between the Mashpee Wampanoag, Aquinnah Wampanoag or other Wampanoag tribes," he

said. "To say that the Mashpee Wampanoag have a historic tie to Taunton, nothing

I see proves that."

Of course, nothing disproves it either, he

said.

In his book, "The Wampanoag Indian

Federation: Indian Neighbors to the Pilgrims," Milton A. Travers wrote about a

Cohannet Wampanoag Tribe, which "occupied the territory including parts of the

present towns of Berkley, Mansfield, Norton and Raynham, and also a portion

within the present city limits of Taunton, Massachusetts."

The Cohannet are not among a list of state-

and federally recognized tribes still in existence.

The Mashpee Wampanoag declined a request by

the Times to release the documentation it presented as part of its application

to the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs and instead issued a statement.

"There are strong ties to the region with

excellent documentary support," tribal council Chairman Cedric Cromwell said.

"Federal and state agencies acknowledge Mashpee connections to the

archaeological record in the Taunton region. The preponderance of scholars who

have written on the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe sees our influence historically as

extending into the Taunton area, and there is linguistic support for that

argument, as well. Beyond this written evidence, we know of this connection

through our oral history, passed down from generation to generation."

false claims?

Other Massachusetts tribes unhappy about the

tribe's federal status are already attempting to poke holes in their historical

data.

At a bureau hearing in Taunton last week,

representatives of the Pocasset Wampanoag and the Massachusett tribe both

testified the Mashpee have no historic links to Taunton.

Pocasset leader George Buffalo Spring

rejected the Mashpee tribe's claims to Taunton land. "The Mashpee leadership

disrespects our Pokanoket ancestors and our lands by improperly making false

claims to reservation shop in Pocasset Pokanoket territories," he said.

But representatives of the Wampanoag Tribe

of Gay Head (Aquinnah), the only other federally recognized tribe in

Massachusetts, defended the Mashpee application, saying all of the Wampanoag

Nation has ties to Southeastern Massachusetts.

Officials at the Robbins Museum in

Middleboro, which is operated by the Massachusetts Archaeological Society and

has an extensive collection of Wampanoag artifacts from the region, were

reluctant to comment on the dispute except to say the region was a hotbed of

Indian activity.

The Times requested the tribe's application

and supporting documents in a Freedom of Information Act filing with the bureau.

Thus far, the bureau has only released documents filed five years ago in support

of taking 539 acres into trust in Middleboro, a proposal no longer on the

table.

But as they did in Middleboro, tribe

historians will likely point to the arrival of the Pilgrims and the "profound

and enduring changes" that resulted in the past 400 years. According to the

historical report drafted by Christine Grabowski for that 2007 application, "the

contemporary Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe descends from a band of Indians that was

part of the historic Pokanoket nation."

Pokanoket nation comprised a group of

"allied sachemships," numbering more than 30, under the leadership of one

Massasoit or supreme sachem, who when the Pilgrims landed was Ousamequin.

The various bands moved around to temporary

settlements on a seasonal basis "rather than specific fixed land-holdings in the

European fashion," Grabowski wrote.

PECK OF BEANS, JACKKNIFE

In his book "Mayflower," Nathaniel Philbrick

writes it was a raid led by Miles Standish in 1623 on the Massachusett tribe and

Massasoit's decision to befriend the Pilgrims that led to what is now referred

to as the Wampanoag Nation.

Massasoit's hold on the region came as a

result of the deaths of some influential Cape sachems, Philbrick wrote. "Over

the next few years, Massasoit established the Indian nation we now refer to as

the Wampanoag — an entity that may not even have existed before this crucial

watershed."

Like the Indians before them, colonists were

drawn to the region — known as Titicut and Cohannet — by the herring-rich

Taunton River.

Elizabeth Pole, according to historical

accounts, purchased land in 1637 for a "peck of beans and a jackknife," moving

from Dorchester to Taunton where there was more room for flocks and herds.

Though there is no official record, the Pole

legend is depicted on the city's seal.

The following year, 46 settlers purchased

land in a deed that bears King Philip's name, and Taunton was

incorporated.

In the years that followed,

Massasoit-controlled Indians and the settlers lived a mostly peaceful existence,

though by 1657 Massasoit's sons became increasingly troubled by the invasion of

colonists into their territories.

"Just a few months later, (Massasoit's son

Wamsutta) refused to part with a portion of the land his father had agreed to

sell" to Taunton, Philbrick wrote.

Philip also did not see things the way his

father did. In the years that followed that 1671 showdown with the colonists in

Taunton, Philip continued to plot his attack, Emery wrote.

It is the murder of Indian John Sassamon in

1675 that triggered the start of King Philip's War — a bloody conflict that

decimated the native population.

Taunton figured prominently in that war. On

June 24, 1675, "Edward Babbitt of Taunton was killed by an Indian of Philip's

band," Emery wrote.

A few days later, it was Taunton that was

designated as a rendezvous point for colonists where they gathered under the

command of Maj. William Bradford of Plymouth, according to Emery's book.

Philip was chased for a little more than a

year in a far-ranging war. In the final days of the conflict, on July 31, 1676,

Capt. Benjamin Church learned King Philip was about to cross the Taunton River

with a view of attacking the towns of Taunton and Bridgewater, Emery wrote. The

next day Church saw Philip on the banks of the river and fired at him, but he

escaped.

On Aug. 6, 1676, with the help of an Indian

informant, 26 Indians were captured in what is now Norton, Emery wrote.

The war ended that month with the killing of

King Philip at Mount Hope in Rhode Island.

All the while, the Mashpee Wampanoag

remained on Cape Cod, staying out of the conflict on land set aside for the

tribe by Richard Bourne, a Sandwich selectman.

Tribes join

After the war, the Mashpee Wampanoag

"absorbed the Coatuits, Satuits, Paupausits, Wakoquits, Ashimits and Weesquob

tribes," Travers wrote.

Mashpee opponents, like the Pocasset and

Massachusett tribes, will argue that's evidence Taunton and other areas of

Southeastern Massachusetts north of the Cape Cod Canal are outside the Mashpee

Wampanoag territory.

James Lynch, an ethno-historian hired by

Pocassets and towns like Halifax to counter the Mashpee Wampanoag claims, has

written the Mashpee can't make the historic and cultural claims necessary

because they don't exist.

"The eminent historian Bernard Lewis once

remarked that there are three kinds of history, recovered, remembered and

invented," Lynch wrote. "Mashpee's claims to Taunton are of the third

sort."

The Mashpee will likely counter they were

part of one nation under Massasoit and they, like the Aquinnah, are the tribes

that survived and continued to govern as a tribe throughout their history.

Unlike King Philip's War, it is a battle

likely to play out in a courtroom.

No comments:

Post a Comment