A consultant's 2004 projection that Salamanca would need to spend about $9.4 million getting ready for the casino was accurate, Vecchiarella said, noting the need for upgrades to electrical and wastewater systems and purchase of a ladder truck for the fire department, which, until the 11-story casino hotel, hadn't needed anything with such reach.

Residents of NY casino town: Not much has changed

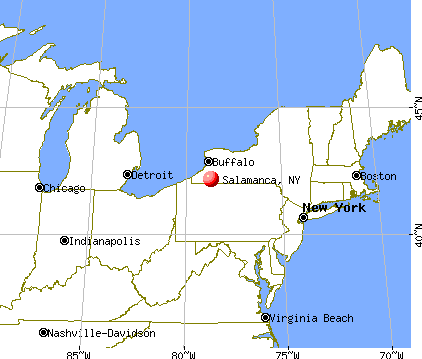

SALAMANCA, N.Y. — Tucked in the foothills of western New York's Allegany Mountains, Salamanca doesn't appear to have changed much in the last 100 years — let alone the last 10 since the Seneca Indian Nation opened a major casino on the edge of town.

With New York about to vote Nov. 5 on a casino proposal that's being promoted as a driver of economic growth in small upstate communities like theirs and the state as a whole, residents here say that while the casino has delivered jobs, the bustle and din of 2,000 slot machines and an average of 8,000 daily visitors, its effect is barely evident outside the gleaming gambling palace walls.

"When the casino came, I thought, 'Great, the town's going to perk up,'" Barbara John said as she worked in a consignment shop near the casino, which towers from the landscape off Interstate 86. "I expected more."

There have been no spinoff restaurants or attractions to keep casino patrons in town, and existing business owners say that except for two hotels, the fast-food chains in the casino's shadow seem to be the biggest winners of any spillover business. Nevertheless, with more than 900 workers, it has become a go-to employer, several residents said, and with its on-site restaurants and concert hall, another option for a night out in a place that lacks even a movie theater.

"In Salamanca, you can't even go buy socks and underwear. There's no place to buy it. There's no stores," said Mayor Carmen Vecchiarella, who described economic development in the community of 6,000 as "stagnant" since the casino.

He hopes that will change with the city's $3.2 million purchase of a 200-acre plot near the casino that is currently landlocked and not serviced by utilities. Salamanca will use casino proceeds to build roads to the site with the goal of accommodating tax-paying developers. There has been talk of locating a water park or shopping plaza there.

"Whatever we can get, it will drive economic development," Vecchiarella said.

If New Yorkers approve four more casinos upstate, an idea pushed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo for more than two years, two communities with harness track racinos — the tiny town of Nichols on the Pennsylvania border west of Binghamton and the booming city of Saratoga Springs — are considered likely contenders. So are several sites in the once-vibrant resort area in the Catskills, including the former Nevele and Grossinger's resorts.

The Seneca Allegany Casino opened May 1, 2004, in this Cattaraugus County city, which is positioned almost entirely on an Indian reservation. It is one of three western New York casino complexes operated by the Seneca Indian Nation under a revenue-sharing agreement with New York state.

The tribe turns over 25 percent of slot machine revenues to New York, which shares a quarter of that with the host communities to help pay their casino-related expenses, make up for lost tax revenues and, with what's left over, undertake new projects.

Salamanca, after expenses are paid, is left with an average of $2 million a year for economic development, said Vecchiarella, who only recently received the last four years of casino payments following resolution of a dispute between the state and Senecas that held up their delivery.

Still, he believes the casino has been good for the community about an hour's drive south of Buffalo.

"It brought employment, activity to Salamanca," he said. "Anything that you bring into an area is a positive because there's something there, something to do."

A consultant's 2004 projection that Salamanca would need to spend about $9.4 million getting ready for the casino was accurate, Vecchiarella said, noting the need for upgrades to electrical and wastewater systems and purchase of a ladder truck for the fire department, which, until the 11-story casino hotel, hadn't needed anything with such reach.

Consultant Rodney Hensel's projection of a 30 percent increase in ambulance calls was low: Town statistics show about a 50 percent increase in emergency medical calls from 2003 to 2012. Vecchiarella said the volume of speeding tickets and other traffic infractions written by police also has grown. On the plus side, there has been no noticeable increase in serious crime, the mayor said, an observation confirmed by statistics.

In 2003, before the casino opened, the town recorded 68 violent crimes, including three rapes, three robberies and 62 assaults, records from the state Division of Criminal Justice Services show. In 2004, violent crime peaked at 99, before falling by nearly half in 2005 and half again in 2006 and leveling off. Last year, there were 25 violent crimes, including three robberies and 22 assaults.

Unemployment in Cattaraugus County, meanwhile, hovers around the statewide average of just over 8 percent, while Salamanca's average rate from 2006 to 2010 was about 10 percent, according to a state comptroller's office report.

It is hard to measure the casino's effect on the city's property taxes because more than 60 percent of Salamanca parcels are tax exempt, a number that grows with each purchase on reservation land by a Seneca Nation member.

Even so, resident Barbara Dexter said the casino has done more harm than good, saying that while she enjoys the casino's buffet and steakhouse, she feels for the problem gamblers who cannot keep away from the slot machines and table games.

"When they're blowing all their money, it's terrible," she said while getting her nails done at a Main Street salon that was empty except for one other patron.

Rachael Ferguson, a casino cook who recently opened a bakery on Main Street, said the casino was not part of her decision to start a business and supplies only the occasional customer.

But she said it is good for the town because it brings people who otherwise might not come.

Fellow casino cook and business partner Carol Bryant agreed. She moved to the Salamanca in February.

Said Bryant: "It's the first place I went to get a job."

http://online.wsj.com/article/AP14d9608f72ac4159a8563c2cb61f45da.html

No comments:

Post a Comment